People

Discovering the work of New Jersey's carpenters and joiners in the provincial and colonial periods is difficult. Very little of their work survives and even less can be associated with particular individuals. Despite the loss of buildings and objects, documentary evidence like account books, wills and probate inventories, deeds and land transfers, court records, and the minutes of religious organizations can inform us about their lives and work. The three carpenters and joiners discussed in this section illustrate the differences between those who worked in towns or in the countryside. Their environments dictated the rhythm and kinds of work they completed. These documents illustrate the local and regional commercial networks in which they worked, particularly those who were members or affiliates of the Society of Friends.

Country versus Town

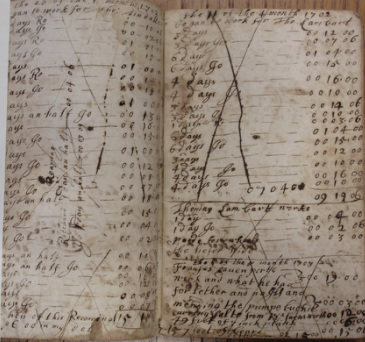

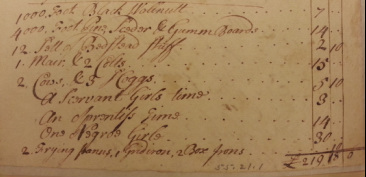

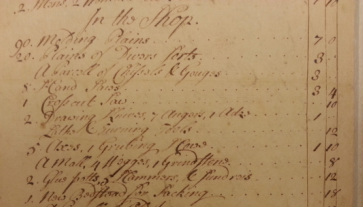

In the images below is a simple account book bound in a recycled seventeenth-century document that likely records the work of carpenter John Tantum (active ca. 1700-25). Tantum was a Friend who participated in the Crosswicks Meeting of Friends located in Chesterfield, NJ, approximately 15 miles to the north of Burlington near the banks of Crosswicks Creek. In 1699, he acquired a plantation in nearby Nottingham Township from fellow carpenter Job Bunting, reflecting the ties of both religion and trade that bound many of the region's skilled craftspeople.(1) His name is inscribed faintly on the book's cover, and within it are entries for carpenter's work beginning in 1701 for various people who were also members of the Crosswicks Meeting. In 1705, Tantum's committee of Friends was tasked with constructing the new meetinghouse at Crosswicks. As one of the community's foremost members, it is not surprising that in 1706 he received the carpentry commission, presumably for interior woodwork.(2)

|

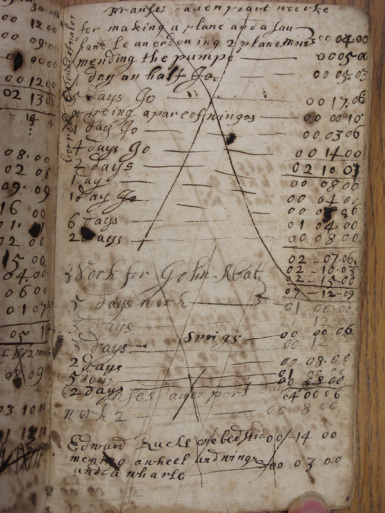

The page at right documents work for three customers, Francis Davenport, John Abat (Abbot), and Edward Rucke, ca. 1703.

Work for Davenport (the first entry on the page) includes "making a plane and saw / handle an (sic) ordoring (sic) 2 planes more / mending the pumpe (sic)." (2 [Although the account is not dated, it occurs after work for Anthony Woodward dated 1703. Woodward was also a carpenter and Friend.] It is possible that Davenport was another member of Tantum's trade, as saws and planes were typical tools of carpentry and joinery. If so, it is possible that Davenport had an upcoming commission since he ordered multiple tools. Other entries of work completed for Davenport document unspecified work at various wages, possibly indicating the employment of an apprentice or journeyman, each with varying skill levels, or work of varying intensities. This entry in particular alludes to a practice of subcontracting in this period that may have been common but remains undocumented. In the final entry on the page, Tantum billed Edward Rucke a "bedstid" (sic), and "mending a wheel and wings [which may refer to a spinning wheel] / and wharfe", indicating that Rucke might've operated a small flat boat, or had a small dock on his property. (3) An entry of four days' work to Davenport at 14 shillings is the equivalent cost of the bedstead, which may be how long it took Tantum, or one of his apprentices, to make it. This hard pine table was used by various clerks of the Burlington Friends' Meeting to record minutes of meetings, and for brides, grooms, and witnesses of the betrothed to sign marriage certificates. It was found during my thesis research in the collection of the Burlington County Historical Society. It may be the same table recounted in a 1698 entry in the minutes of the Burlington Meeting tasking two Friends--Isaac Marriott and Benjamin Wheate--to provide a pine table for the meeting's use. It is possible that Wheate completed joinery work in addition to his more formal occupation as a cordwainer, or shoemaker, but records show that Marriott was a joiner by profession and it is likely that he made this table.(4)

Marriott left London where he was born and raised before arriving in Burlington in 1680. He would have been twenty and nearing completion of his apprenticeship upon his arrival.(5) Land records indicate Marriott occupied a lot very close to the waterfront in Burlington. Although in its infancy, the bustling port of Burlington must have been reminiscent of former home. As a resident of the town of Burlington, Marriott likely had a shop where he worked, and possibly also where he sold dry goods and sundries. Like his country counterparts, town carpenters and joiners often acted in a retail capacity as merchants to supplement their woodworking trade. |

In 1702, Tantum worked nearly exclusively for Thomas Tindall and Thomas Lambert, also major members of the Crosswicks Meeting. Like other accounts, the work is largely undifferentiated with only days of work and rates of pay billed. Tindall's bill of £15 (at left) and Lambert's of £9-19s.-6d. (at right) account for extensive work of perhaps one or more men, indicating larger jobs. Many entries end with "Jo" or "Ro", possibly abbreviations for apprentices' names.

The seasonal rhythms of farming dictated the work of Tantum and other country carpenters. Tantum's account of work completed for Tindall began at the end of March ("26th of 1st month" in the Julian calendar), at a time when it would have been conducive to working outdoors. This account of nearly one hundred days' work implies a large job, possibly interior woodwork or house framing. Many accounts illustrate the seasonality of woodworking, beginning in March or April and spanning three or four months before the fall harvest when the days were longest. |

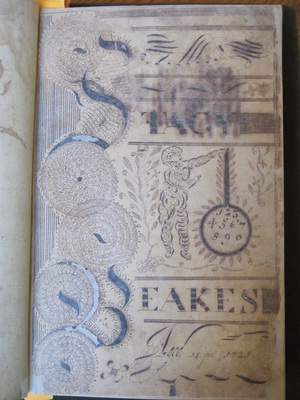

Documents often contradict or challenge our assumptions, especially in the laboring trades like carpentry and joinery. The examples of two related craftsmen--William Beakes III, a joiner, and his half-brother, Stacy Beaks, a carpenter--illustrate the differences in opportunity and importance of educational training to these occupations. Quakers were concerned about the lives of their teenage members, and feared waywardness in this trying time of life. Formalized education through exercise books was not a means to an end; it was a supplement to the more important educational exercise: apprenticeship. It seems, however that these attitudes differed between the town and the countryside, and might have also changed over time, attested by the words of each William and Stacy in their wills.

|

|

William Beakes (or Beake) III (1691-1761) was born in Bucks County to an important local family in the Friends' community. William's grandfather was a founder of the first meeting in the Pennsylvania colony, known as the Falls Meeting.

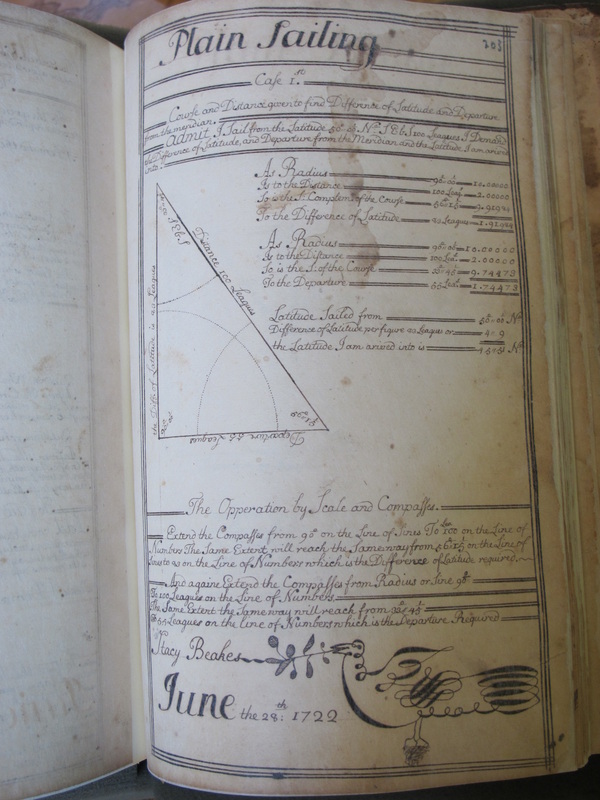

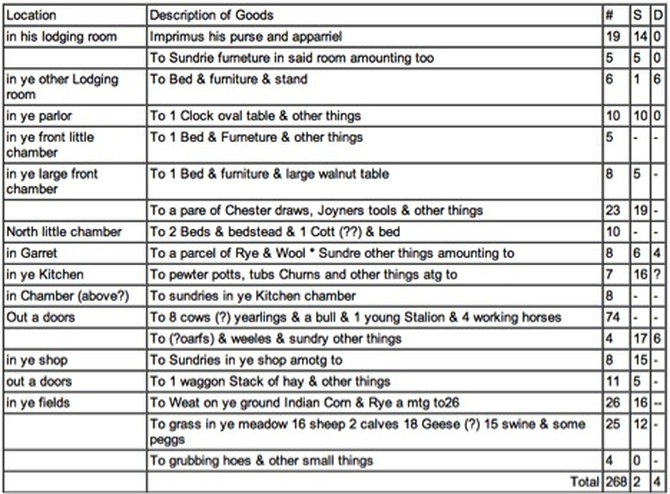

As a teenager, William completed an apprenticeship in Philadelphia with Friend and joiner William Till, who died in 1711.(6) In the decade following the elder joiner's death, Beakes created three nearly identical joined chests of drawers seen in the slideshow at left. Two bear Beakes' signature, while the third is inscribed by its original owner in 1720, who credits Beake as the maker.(7) This final chest in the Dietrich American Foundation is inscribed by Sarah (Foulke) Thorn, who was living in Burlington County in 1720. Although there is no documentary evidence that places Beakes in Chesterfield where the Foulkes lived, it seems likely that Sarah's father, Thomas, used a local joiner like Beakes for this commission. William's mother died during his apprenticeship, and his father married Ruth Stacy, daughter of Mahlon Stacy, a tanner from Yorkshire and one of the wealthiest men and largest landowners in provincial New Jersey at that time.(8) The marriage of William's father to Ruth Stacy gave a whole new level of prominence to the Beakes family. In approximately 1706 their first child, Stacy, was born. At left is the frontispiece from Stacy's mathematical exercise book he used from 1721-22 when he was approximately 15 or 16. The calligraphy illustrates the steady hand and detailed eye of a craftsman, while the exercises calculating interest and types of bartering indicates the accounting knowledge needed to manage the finances of his large cabinetmaking and carpentry shop in bustling Trenton later in life. No doubt because of Stacy's family's wealth, he was given an excellent education. So few of these books survive that can be ascribed to a singular maker, it is hard to know if the extent of Stacy's accounting training was typical for tradesmen, or is more indicative of someone of the Stacy family's wealth. Other exercise books belonging to young men and women in colonial America show they learned similar arithmetic.(9) If this was typical, it indicates a level of learned education for carpenters and joiners not previously known. This page from the exercise book (at left) illustrates a geometry problem involving plain sailing. Water-borne transportation was essential in this region and era, so this exercise had immediate and practical application. The calligraphic flourish of a bird holding an olive branch adjacent to Beaks' signature was a typical motif of the period, often found decorating the backs of spoons. At the time of his death in 1745/46, Stacy had built a large cabinetmaking or carpentry enterprise. His real property (not including debts owed to the estate) was valued at £219-18s.-0d.(10) In an inventory of his estate (below), nearly one-tenth of the total sum was in tools, including over 110 planes, five handsaws, chisels and gouges, as well two glue pots and hammers, referring to tools used in attaching veneers. The woods in his shop include one thousand feet of black walnut and four thousand feet combined of pine, gum, and cedar boards that accounted for another £21, indicating a shop of prodigious production that could've included interior woodwork as well as furniture. |

Stacy Beaks died while actively engaged in carpentry, or as the master of a carpentry shop. His half-brother, William III, had moved to Upper Freehold Township to the east of Chesterfield by this time. When William drafted his will in 1761, he still identified himself as a joiner, implying that he, too, might have still been active in joinery. His inventory, transcribed below, shows that his joiner's tools as well as two chests amounted to nearly one tenth of his estate's value. Plantation or grazing lands and livestock accounted for nearly one half of William Beake's estate, in contrast to Stacy, who had lived and worked in Trenton at the time of his death.

Despite these differences, education was clearly of great importance to both craftsmen, and each provided specifically for the continued education of family members in their wills. William Beakes specified that "my mind & will is for ye better Enabling my dear wife to bring up & Educate my two grandsons William & John Morford I give her the further sum of twenty pounds money as above said to be levey'd out of my estate." (11)

Living and working in the town of Trenton in the early eighteenth century, Stacy Beakes was attuned to the education necessary for his children to thrive in business and to make attractive partners for future suitors. He made a similar provision in his will but referenced specific levels of education he desired both his son and daughters to obtain: "my will is that my Son Stacy Beakes, shall be brought up and Educated to read and write and sipher (sic) through Vulgar Arithmatick (sic) and at the age of fourteen years to be put an apprentice to Learn some good trade as he may Chuse (sic), and also my three Daughters to be brought up and Educated to read, write and sipher (sic) through the rule of Three." (12)

Living and working in the town of Trenton in the early eighteenth century, Stacy Beakes was attuned to the education necessary for his children to thrive in business and to make attractive partners for future suitors. He made a similar provision in his will but referenced specific levels of education he desired both his son and daughters to obtain: "my will is that my Son Stacy Beakes, shall be brought up and Educated to read and write and sipher (sic) through Vulgar Arithmatick (sic) and at the age of fourteen years to be put an apprentice to Learn some good trade as he may Chuse (sic), and also my three Daughters to be brought up and Educated to read, write and sipher (sic) through the rule of Three." (12)

Footnotes

(1) "1699 Nov. 7. Deed. Job Bunting, late of Crosswicks Creek, now of Buck Town, Bucks Co., Penna: carpenter, to John Tantum of Crosswicks Cr., Burlington Co., carpenter, for a plantation of 240 acres in Nottingham Township." See CROSS, p. 526.

(2) Joseph Middleton, "Friends and Their Meetinghouses at Crosswicks," PMHB 27:3 (1903): 340-345.

(3) I am grateful to Joan Berkey for her insights about the accounting in this book.

(4) See Minutes of Burlington Monthly Meeting (microfilm, p. 14). Friends Historical Library.

(5) In W. J. Buck's manuscript Records of Burlington and Mt. Holly Monthly Meeting 1678-1872, under section 'Certificates of Removal to Burlington,' Isaac Marriott’s certificate from the Men's Meeting in London is dated 12th mo. 7 1680, coming from Holborne in London. He is listed as a joyner, son of Richard of Wappingham in Northamptonshire. See p. 237.

(6) Till is recorded as the master of William Beaks Jr. in the will of Susannah Worrilaw dated 1710. See Philadelphia Wills and Inventories (microfilm), #172-B.

(7) The inscription reads "Sarah Thorn her Draws / made by Wm Beakes this 14th of 12th mo. 1720."

(8) In Lewis D. Cook, Chesterfield Monthly Meeting. Burlington County, New Jersey: Intentions of Marriage and Certificates of Removal, 1685-1786 (1970, p. 2) in the collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, William Beakes II. and Ruth Stacy declared their intentions to marry (possibly the second declaration) on May 3, 1705.

(9) Although later, the exercise books of Peggye Clayton and Martha Ryan, young women from North Carolina, illustrate similar kinds of arithmetic. For additional exercise books, see the Joseph Downs Collection at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.

(10) Inventory of Stacy Beaks, 1745/46. Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library. Col. 61, 55.21.1.

(11) Will and inventory of William Beakes III, 1761. New Jersey State Archives, Book B. 11 / p. 63, will 2581-2588 M.

(12) Will of Stacy Beaks, 1745/46. New Jersey State Archives, Book B. 5 / p. 264, will 187 J.

(1) "1699 Nov. 7. Deed. Job Bunting, late of Crosswicks Creek, now of Buck Town, Bucks Co., Penna: carpenter, to John Tantum of Crosswicks Cr., Burlington Co., carpenter, for a plantation of 240 acres in Nottingham Township." See CROSS, p. 526.

(2) Joseph Middleton, "Friends and Their Meetinghouses at Crosswicks," PMHB 27:3 (1903): 340-345.

(3) I am grateful to Joan Berkey for her insights about the accounting in this book.

(4) See Minutes of Burlington Monthly Meeting (microfilm, p. 14). Friends Historical Library.

(5) In W. J. Buck's manuscript Records of Burlington and Mt. Holly Monthly Meeting 1678-1872, under section 'Certificates of Removal to Burlington,' Isaac Marriott’s certificate from the Men's Meeting in London is dated 12th mo. 7 1680, coming from Holborne in London. He is listed as a joyner, son of Richard of Wappingham in Northamptonshire. See p. 237.

(6) Till is recorded as the master of William Beaks Jr. in the will of Susannah Worrilaw dated 1710. See Philadelphia Wills and Inventories (microfilm), #172-B.

(7) The inscription reads "Sarah Thorn her Draws / made by Wm Beakes this 14th of 12th mo. 1720."

(8) In Lewis D. Cook, Chesterfield Monthly Meeting. Burlington County, New Jersey: Intentions of Marriage and Certificates of Removal, 1685-1786 (1970, p. 2) in the collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, William Beakes II. and Ruth Stacy declared their intentions to marry (possibly the second declaration) on May 3, 1705.

(9) Although later, the exercise books of Peggye Clayton and Martha Ryan, young women from North Carolina, illustrate similar kinds of arithmetic. For additional exercise books, see the Joseph Downs Collection at Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library.

(10) Inventory of Stacy Beaks, 1745/46. Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library. Col. 61, 55.21.1.

(11) Will and inventory of William Beakes III, 1761. New Jersey State Archives, Book B. 11 / p. 63, will 2581-2588 M.

(12) Will of Stacy Beaks, 1745/46. New Jersey State Archives, Book B. 5 / p. 264, will 187 J.