Materials

“There is a great plenty of working timber, as oaks, ash, chestnuts, pine, cedar, walnut, poplar, fir, and masts for ships, with pitch and pine resin, of great use and much benefit to the country.” ~ Gabriel Thomas, 1698 (1)

Craftsmen immigrated to the Delaware Valley, and New Jersey particularly, for principally economic and religious reasons. Gabriel Thomas's quote above from a promotional pamphlet published in 1698 highlights the desirability of certain woods, and New Jersey's agriculture and ecological diversity was attractive to woodworkers whose livelihood was based on the abundance of these raw materials. Water-driven mills for processing corn and other grains were among the first structures other than houses erected in small settlements established by these immigrants. Saw mills soon followed, built upon the colony's numerous creeks and rivers that traverse the region. These mills both increased the speed of wood processing and were valuable enterprises that aspiring carpenters and joiners, like William Hall, Sr. in Salem, sought to own in total or part. (2) By the 1690s, saw mills existed in Salem County in West Jersey, and Essex and Monmouth Counties in East Jersey. (3) Thomas further noted that "Timber-River, alias Glocester River, which hath its name (also) from the great quantity of curious Timber, which they send in great float to Philadelphia, a city in Pennsylvania, as Oaks, Pines, Chestnut, Ash, and Cedars."(4) These were among the most important woods that formed part of New Jersey's coastal and transatlantic timber export trade.

This section discusses the raw materials used in the houses and buildings created during periods of early settlement. These woods, as well as those of fruit and sap trees, were also found in furniture made throughout the Delaware River Valley and, by extension, in New Jersey.

Woods for Daily Life

Craftsmen immigrated to the Delaware Valley, and New Jersey particularly, for principally economic and religious reasons. Gabriel Thomas's quote above from a promotional pamphlet published in 1698 highlights the desirability of certain woods, and New Jersey's agriculture and ecological diversity was attractive to woodworkers whose livelihood was based on the abundance of these raw materials. Water-driven mills for processing corn and other grains were among the first structures other than houses erected in small settlements established by these immigrants. Saw mills soon followed, built upon the colony's numerous creeks and rivers that traverse the region. These mills both increased the speed of wood processing and were valuable enterprises that aspiring carpenters and joiners, like William Hall, Sr. in Salem, sought to own in total or part. (2) By the 1690s, saw mills existed in Salem County in West Jersey, and Essex and Monmouth Counties in East Jersey. (3) Thomas further noted that "Timber-River, alias Glocester River, which hath its name (also) from the great quantity of curious Timber, which they send in great float to Philadelphia, a city in Pennsylvania, as Oaks, Pines, Chestnut, Ash, and Cedars."(4) These were among the most important woods that formed part of New Jersey's coastal and transatlantic timber export trade.

This section discusses the raw materials used in the houses and buildings created during periods of early settlement. These woods, as well as those of fruit and sap trees, were also found in furniture made throughout the Delaware River Valley and, by extension, in New Jersey.

Woods for Daily Life

|

Stand of pine trees, Apple Pie Hill, Burlington County, NJ

Courtesy F. A. Martin, Wikimedia Commons Because they were plentiful and durable, pines were favored for interior carpentry--and even decorative trim--throughout houses the southern half of New Jersey (formerly know as the province of West Jersey). From interior doors to baseboard moldings and even built-in furniture--like a corner cupboard from a Burlington County pattern-ended brick house--pine was commonplace. Carpenters and joiners favored hard pine, commonly called 'yellow pine', for making joined or six-board chests for storage, and as a secondary cabinet wood for the sides of drawers, their runners, and their blades. The image below shows a hard pine chest made in the eighteenth century (at left), and a hard pine board used for a drawer side (at right), with its characteristically straight, darkly striped late growth visible.

|

Of singular importance to settlers of New Jersey and their economy was timber. Timber products were used to construct ships, and cooperage or barrels, not just houses. Woodlands were also used to power early furnaces for the bog iron and glass industries established in the southern parts of the colony.

Pines in particular were plentiful in Burlington, Cumberland, and Salem Counties located in the Inner Coastal Plain. Pitch pines (Pinus rigida) in forests like this one located at Apple Pie Hill found throughout the southwestern part of the colony were valued highly for making pitch and turpentine also used in shipbuilding. The province's leaders were quick to protect timber for these functions through some of the earliest legislation passed by the General Assembly. |

|

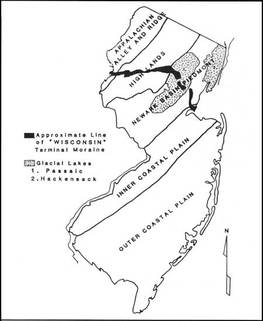

Central to New Jersey's ecological riches is its geological history, which also dictated some of the natural boundaries that first divided the region east of the Delaware that became New Jersey. This map illustrates the rough geographical division of New Jersey's landscape. The Outer Coastal Plain takes up nearly one half of the state's size, and is the final destination of many tributaries branching off the Delaware River that terminate in swamps and marshland in the Pine Barrens region. Here, sandy soil is conducive to growing coniferous species, like hard pine, and Atlantic white cedar. Large tracts of timber from this geographic region were harvested for shipbuilding, and fueled the numerous iron furnaces and glassworks that took hold early in the province's history.

The Inner Coastal Plain consists of drier, arable farmlands. Many of the first settlers to the West Jersey province resided in this narrow corridor that includes present-day Camden, Burlington, Trenton, and Freehold. |

|

Atlantic white cedar (Chamaecypris thyoides (L.) was another coniferous species crucial to the building and furniture trades. This tree often grew tall and straight in dense stands, favoring the Outer Coastal Plains' sandy soils. Because of that biological preference, white cedar grows in a narrow strip of the East Coast from Maine to Florida, and then west from northern Florida to Mobile, Alabama. The densest stands are found in New Jersey, northwestern Florida, and Eastern North Carolina. This growing map published by the USDA illustrates its favored growing regions.

House carpenters in New Jersey used cedar for roof timbers, and cedar shingles were found by the hundreds or thousands in the inventories of carpenters and house owners from New Jersey to Philadelphia. Cedar shingles, no more than 4-6" in width, were laid vertically and nailed atop one another. Although not the first cedar shingles laid in the 17th century, these examples below from the Thomas Revell House (1691) in Burlington reflect the arrangement and dimension of shingles made in the 17th century. |

Like hard pine, white cedar was widely favored as a secondary cabinet wood throughout the Delaware Valley. Cedar's prevalence in the region's furniture has led furniture historians specializing in this region's material culture to mistakenly ascribe this furniture to Philadelphia, although cedar was actively crossed the Delaware River from New Jersey to Philadelphia. Instead, it seems much more likely that this wood was favored by carpenters and joiners working on both sides of the river, and throughout the region. Chests of drawers, dressing tables, high chests, and valuables boxes (referred to in the present day as a spice box) can all contain cedar, helping us to understand both its profusion in the landscape and a wider skilled awareness of its value to specific functions.

In the example of a drawer bottom shown on the left, a few boards are laid with the wood's grain running from the drawer front to its rear and glued together (known as a 'butt joint'), then nailed around the perimeter. This is a common method of finishing a drawer bottom in the earliest period of furniture-making in this region. Furniture-makers strategically used cedar for the backs and sides of drawers in large case pieces. The wood was structurally strong, resistant to rot, and was less dense, making the drawers lighter than if a heavier wood like white oak or tulip poplar was used. English-immigrant joiner John Head, who worked in Philadelphia, used cedar for drawer sides, backs, and bottoms in many of his chests of drawers, like this example at left. |

'All which there is plenty for the use of man...'

William Penn's promotional literature written in 1683 to sell his colony of Pennsylvania imparted to potential settlers the bounty and variety of timber species present in 'Penn's Woods'. (4) Many of these trees, as attested by Gabriel Thomas and others, also grew plentifully in New Jersey. Penn notes specifically "black walnut, cedar, cypress, chestnut, poplar, gum wood, hickory, sassafras, ash, beech and oak of divers sorts as red, white & black; Spanish chestnut and Swamp [chestnut]." In addition to white cedar and hard pine, many of these woods were used in furniture made in the Delaware River Valley as illustrated by the examples below. When available, links to objects in public collections have been provided.

William Penn's promotional literature written in 1683 to sell his colony of Pennsylvania imparted to potential settlers the bounty and variety of timber species present in 'Penn's Woods'. (4) Many of these trees, as attested by Gabriel Thomas and others, also grew plentifully in New Jersey. Penn notes specifically "black walnut, cedar, cypress, chestnut, poplar, gum wood, hickory, sassafras, ash, beech and oak of divers sorts as red, white & black; Spanish chestnut and Swamp [chestnut]." In addition to white cedar and hard pine, many of these woods were used in furniture made in the Delaware River Valley as illustrated by the examples below. When available, links to objects in public collections have been provided.

Footnotes

(1) “An Historical and Geographical Account of the Province and Country of West-New-Jersey in America, by Gabriel Thomas, 1698," reprinted in Albert Cook Myers, ed. Narratives of Early Pennsylvania, West New Jersey and Delaware, 1630-1707. Original Narratives of Early American History. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1912, 349-50.

(2) Will. William Hall, Sr. dated 1713. New Jersey State Archives, Lib. Book I, p. 457.

(3) Thomas Hancock of Hancock's Bridge, Salem County, erected a saw mill by 1686 (see Historic Themes and Resources within the New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail, 96). Samuel Marsh of Elizabeth Town, NJ sold a partial share of his saw mill to Peter de Siguey in a bond dated Feb. 11, 1684/85 (CROSS, p. 88; Liber Book A, p. 413). In 1690, Thomas Gordon was granted multiple tracts of land in Monmouth Co. including a fifty-acre parcel below a saw mill that belonged to Thomas Leonard, possibly of Shrewsbury, who died 1714 (CROSS, p. 190; East Jersey Deeds, Liber D, dated May 24, 1690).

(4) Ditto FN (1) above.

(1) “An Historical and Geographical Account of the Province and Country of West-New-Jersey in America, by Gabriel Thomas, 1698," reprinted in Albert Cook Myers, ed. Narratives of Early Pennsylvania, West New Jersey and Delaware, 1630-1707. Original Narratives of Early American History. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1912, 349-50.

(2) Will. William Hall, Sr. dated 1713. New Jersey State Archives, Lib. Book I, p. 457.

(3) Thomas Hancock of Hancock's Bridge, Salem County, erected a saw mill by 1686 (see Historic Themes and Resources within the New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail, 96). Samuel Marsh of Elizabeth Town, NJ sold a partial share of his saw mill to Peter de Siguey in a bond dated Feb. 11, 1684/85 (CROSS, p. 88; Liber Book A, p. 413). In 1690, Thomas Gordon was granted multiple tracts of land in Monmouth Co. including a fifty-acre parcel below a saw mill that belonged to Thomas Leonard, possibly of Shrewsbury, who died 1714 (CROSS, p. 190; East Jersey Deeds, Liber D, dated May 24, 1690).

(4) Ditto FN (1) above.