From Province to Colony, 1670-1730

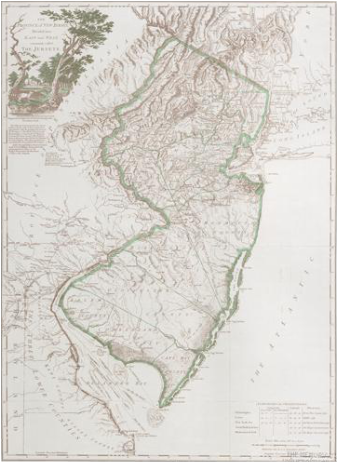

New Jersey at the time of the signing of ratification of the Constitution

William Faden, 1778, reprinted 1937 (acc. no. 01886 gr) Image courtesy of the Historic Map Collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware |

Why New Jersey?

The study of furniture as material culture has been closely tied to connoisseurship and the antiques marketplace for decades. Collectors (and most historians) have taken a hyperlocal approach to studying and classifying furniture made in British colonial North America. Fixated on identifying individual makers and shops, or production in towns or major port centers, they ascribed historical significance and real value to furniture that could be tied to major individuals or places. Very little furniture in the marketplace or in museums has been signed or can be firmly attributed to a specific maker, leaving the majority of extant furniture understudied. Few historians have looked categorically at unattributed furniture possibly made across political boundaries to encompass a distinct geographic region. I have sought to understand furniture-making across the Delaware Valley, a region historically dominated by Philadelphia, but which includes large sections of New Jersey, whose furniture had not been the subject of significant study since 1959. The Lenni Lenape inhabited the lands of this region, including the terrain east of the Delaware River, when Dutch and Swedish traders arrived and established themselves in the 17th century. After the 1660s, a new wave of English, Scots-Irish, and Irish immigrants arrived, pursuing economic and religious freedom, including those who departed colonies in New England, Flushing, Long Island, and the Caribbean settled earlier by the Society of Friends, or Quakers. They continued their traditions of Anglo-European craftsmanship using New Jersey's rich forests of white cedar, hard pine, oak, walnut, and other local woods. Plentiful forests across the Delaware River Valley sourced the timbers to frame and shingle their houses and by which to construct furniture. Members or sympathizers with the religious group the Society of Friends made up the largest portion of the immigrants to the Jersey provinces in the 1670s to 1690s. Beginning with the arrival of the Griffin to John Fenwick's colony (later known as Salem) in 1675, Quakers came to the West Jersey province by the hundreds. Promotional literature published in London, Dublin, and Edinburgh advertised the ecological and agricultural wealth found east of the Delaware River. Wages in the provincial capital, Burlington, rivaled those of London, promising a good earning for those who were industrious and capable of financing the Atlantic crossing. Carpenters across the colony worked in towns and rural settings. Those who lived in larger towns, like Burlington or Elizabethtown (now Elizabeth), might have specialized in house carpentry or joinery, while their counterparts in the rural, plantation hinterlands were 'jacks' of many woodworking skills. Account books and court and estate records recount their work that varied from mending buckets and making bedsteads to hauling salt and framing houses. This project takes a brief look at the early woodworkers of New Jersey during its first sixty years as an English province, then colony. Very little of the furnishings made in this period has survived, but buildings, account books, probate inventories, and court records restore their historical presence. |